King Faisal, known as a progressive and reformer, reigned November 2, 1964-March 25, 1975;

ironically, both died by politico-religious assassination

Last year I wrote about the basics of hajj, pilgrimage, the 5th Pillar of Islam, obligatory once in a lifetime for those Muslims who can afford it and are in good enough health. In that post, Saudi Arabia and Hajj, illustrated with pictures from the 2008 Hajj, I included research from Harvard, “Estimating the Impact of the Hajj: Religion and Tolerance in Islam's Global Gathering”, showing that the profound effects on individual hajj pilgrims extend to others in their home communities. These benefits are primarily those of contact with pilgrims from diverse races, ethnicities, cultures, and social circumstances.

Such a communal experience during the pilgrimage--living near to each other, ablutions and prayers together, circumambulating the Kaaba all dressed the same, men in white, women in white or black, all together shoulder to shoulder, all submitting to the same rituals, to the 5th Pillar of Islam, to Allah--leads to greater knowledge of and tolerance of others, and greater egalitarianism with lasting changed attitudes, behaviour, social implications for themselves and the communities which they rejoin and where they have respect and influence.

Those who have been to Hajj describe it as a deeply moving spiritual experience connecting them more consciously to Allah, but also as a revelation of their connectedness with pilgrims from every part of the ummah. Many have experienced a transformation not only in their deepened experience of faith, but in some aspect of their psychological and social life.

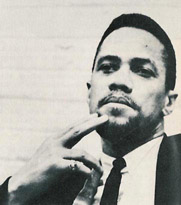

For one famous pilgrim, Malcolm X, the experience of hajj was transformative of his understanding of and adherence to Islam, from the beliefs of the Nation of Islam to becoming a Sunni Muslim. It also transformed his role within the civil rights movement, leading him out of the more narrowly race-based Nation of Islam, to founding both religious organization Muslim Mosque, Inc., for all African Americans of Islamic faith, and the secular Organization of African American Unity (OAAU).

Most are familiar with the story of Malcolm Little, who became Malcolm X, then El-Hajj Malik El- Shabbaz. Malcolm Little was born May 19, 1925 in Omaha, Nebraska, to a lay Baptist preacher and Pan-African black pride activist, Earl Little. While his mother was pregnant with Malcolm she was threatened by Ku Klux Klansmen; due to further threats against the family they moved to Milwaukee then Lansing; Michigan when Malcolm was 2; their Lansing house was burned by white supremacists when Malcolm was 4; his father was killed by white supremacists of the Black Legion, a splinter group of the KKK, when Malcolm was 6

When Malcolm was 13 his mother was declared mentally incompetent, and her children, including Malcolm sent to separate foster homes. He lived with a series of white foster families until at age 16 he joined a half-sister in Boston.

Though a good student, Malcolm had dropped out of Grade 8 when a white teacher told him he couldn't aspire to a career as a lawyer because a trade was more fitting for a 'nigger'. In Boston he took various odd jobs, then drifted from city to city including Harlem where he made a living from drug dealing, gambling, racketeering, robbery, and procuring (pimping). He returned to Boston when he was 21 and was part of a burglary gang that specialized in break and enter and theft in rich white houses. When he was 21, he was arrested, convicted of larceny and sentenced to 8-10 years.

Malcolm Little became Malcolm X on joining the Nation of Islam, after his release from prison. NOI members replaced their surnames, which were most often those of their ascendants' slave owners, with an X, as a rejection of the 'white man's name', and in favour of an unknown African one. Malcolm's journey toward the Nation of Islam began in prison, under the influence of a fellow prisoner who encouraged him to continue his education, and of family members who had already joined the NOI.

Good-looking, intelligent, articulate, and charismatic, Malcolm X rose rapidly in the NOI and was one of its best known members. He preached the teachings of the NOI, Black supremacy, White evil, and the necessity of social revolution, 'by any means necessary'. The willingness to embrace violence set the NOI against other civil rights movements, that of Dr Martin Luther King Jr, based on Gandhi's passive resistance, most notably. Malcolm X was almost immediately monitored by the FBI for his favourable comments about Communism, and rapidly came to be feared by average Whites as he was more and more often interviewed in print, on radio, and on television.

El-Hajj Malik El-Shabbaz was Malcolm X's chosen name as a Sunni Muslim, after his pilgrimage to Makkah. Though Shabbaz became the name of his wife and children as well as his own legal name at death, he is best remembered as Malcolm X. His own book with Roots writer Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, described as one of the 10 most influential books of the 20th century by Time Magazine, memorializes him as such. So does the famous film by activist African-American director, Spike Lee, Malcolm X, starring Denzel Washington. An X on black, X, became the logo for the film. Others just speak of 'Malcolm', and their listeners know who they mean.

Malcolm X, Prince Faisal Al-Saud and Hajj- April 1964/Dhu Al Hijji 1383

Malcolm X arrived in Jeddah on April 13, 1964 with the intention of proceeding to Makkah, but there was concern that his hajj visa was not in fact valid, due to his adherence to the Nation of Islam, which believes there was a Muslim prophet after the Prophet Mohamed, in the person of Elijah Muhammad. His American passport and inability to speak Arabic made Saudi authorities further question whether Malcolm X was a Muslim. He was held back from his group.

When he had been given his hajj visa, Malcolm X was also give a copy of the book The Eternal Message of Muhammad by Abdul Rahman Hassan Azzam, and while waiting in Jeddah he called Azzam's son, who had him released from official custody where he had been for 20 hours. After visiting the son's home, and meeting Azzam Pasha, the latter gave Malcolm X his own suite at the Jeddah Palace Hotel. The next morning Prince Faisal Al-Saud's son Muhammad visited with the news that Malcolm X was to be a state guest of Prince Faisal. Malcolm X was accompanied to Makkah and completed the Hajj on April 19, 1964. After that, he was received by Prince Faisal himself.

The experience of his trip to Jeddah, his readings, and particularly performing Hajj with Muslims of all stations from around the world radically altered Malcolm X's beliefs about Islam, leading him to embrace Sunni Islam, and on race, leading him to embrace a more moderate and collaborative political stance. Both aspects led him out of the Nation of Islam, and arguably led to his death, assassinated by NOI members for his beliefs and political power.

In the course of research on a different topic entirely, I came across a little known interview of Malcolm X by one of Canada's then premier journalists, Pierre Berton, on his famous half hour interview program for the CBC. Malcolm X was brought to Canada by the CBC to participate in its iconic current affairs program Front Page Challenge, where a panel of famous journalists, including Pierre Berton, would ask questions to identify the mystery guest, and then interview the person on the relevent headline-making issue.

Both interviews follow, in chronological order, after a slightly earlier feature piece and interview with Malcolm X by Ebony writer and editor Hans J. Massaquoi. The 3 interviews are evidence of the lasting transformational effect of Hajj, and the extension of that transformation to the broader community, in a process begun with Malcolm X's Letter from Mecca, written for public distribution during his 11 day stay at the Holy Site.

by Hans J. Massaquoi

Ebony, September 1964, pp38-46 [Reproduced in full, text and pictures, here on Google Books]

Reprinted, 'Mystery of Malcolm X-Interview', by Hans J. Massaquoi, Ebony 1993, online here at Find Articles from BNET

Shortly before his death, enigmatic leader revealed his changed views on race and the liberation struggle

A HEAVY, dark-blue sedan stops at the curb on Seventh Avenue where a small group of men, women and children stands in sullen silence around a pile of shabby furniture--the worldly possessions of a family without a home. The scene is a familiar one for that part of Harlem where poverty has forced thousands of human beings to co-exist with evictions, hunger and rats. It is a familiar and hated as the patrols of White rookie cops who casually saunter by, their billy clubs twirling with suggestive ease.

At the sight of the driver, the expressions of hopeless rage on the faces of the little crowd melt into broad, deferential smiles. 'Salaam aleikum, Brother Malcolm.' 'Salaam aleikum.'

With a wide, good-natured grin that bares a flawless set of large teeth, the reddish complexioned, scholarly looking man behind the wheel returns the Muslim greeting. With deep-set, penetrating eyes behind a pair of horn-rimmed glasses he surveys the familiar scene. His voice sounds reassuring as he reminds the people to attend 'a very important meeting tonight.' After another exchange of 'salaams,' he pulls from the curb and is soon swallowed up by the dense traffic and the glare of the sun.

Around the nation, the name Malcolm X triggers mixed emotions, but among the dispossessed masses of Harlem, it inspires devotion and hope. Since his ouster from the Black Muslim cult early this year--ostensibly for calling President Kennedy's assassination a case of 'chickens coming home to roost'--he has pitted his own prestige against that of his former chief, Elijah Muhammad, in building a following of his own. In the process, he has ripped the Black Muslim movement into two hostile camps whose bloody encounters have become the order of the day. Purged from the No. 2 spot he used to occupy in the Black Muslim hierarchy, he is now reaching for higher stakes-- participation in the Black revolt.

The entry of the firebrand advocate of bloody retaliation into the rights struggle which, as far as Blacks are concerned, has been largely non-violent, is viewed by many Blacks and Whites with grave concern. But in Harlem's tenements, where the pacific voice of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is but a whisper, the new power bid of Malcolm X is welcome news.

Minutes after leaving the eviction site, Brother Malcolm--as he prefers to be called--turns up at a small restaurant on West 135th Street. There is nothing about his ingratiatingly polite demeanor, or his loose-jointed six-foot-three frame to betray that it is he who suggests taking on Mississippi's Ku Klux Klan with armed guerrillas. His impeccable seer-sucker suit and brief case make him a dead ringer for an up-and-coming attorney, certainly not for a man about to enter a revolt.

With gangling, yet purposeful strides, Brother Malcolm walks to the rear of the narrow room where he joins a Black reporter. Between sips of coffee and incessant doodling he ponders the reporter's questions, then lets loose with a barrage of replies.

'Is it true,' the reporter wants to know, 'that since your recent pilgrimage to Mecca you no longer hold to your earlier belief that all Whites are evil?'

Malcolm X looks thoughtfully at his large expressive hands. 'True--my trip to Mecca has opened my eyes. I no longer subscribe to racism. I have adjusted my thinking to the point where I believe Whites are human beings--as long as this is borne out by their humane attitude toward Negroes.'

'Were you serious when you proposed to send armed guerrillas into Mississippi to protect civil rights workers?'

'Dead serious. We will not only send them to Mississippi, but to any place where Black people's lives are threatened by White bigots. As far as I am concerned, Mississippi is anywhere south of the Canadian border.'

'How do you intend to carry out these plans?'

With my new Organization of Afro-American Unity, a non-religious and non-sectarian group organized to unite Afro-Americans for a constructive program toward attainment of human rights.'

'How strong, would you say, is your group at this point?'

Again that ingratiating smile. 'I'm not saying. You know, the strongest part of the tree is the root. Once you expose the root, the tree dies. You never expose your strength.'

'Are you prepared to cooperate with other civil rights groups?'

'We will cooperate with any group that is for Black.'

'Will you accept White members in your new organization?'

Malcolm X stiffens. 'Definitely not.' Then, after a characteristic tuck at a stray whisker in his reddish-blond moustache, he adds: 'If John Brown were still alive, we might accept him. But I'm definitely not interested in non-violent Whites or non-violent Blacks. If you show me a non-violent Negro, I'll show you a Negro whose reflexes don't work, one who needs psychiatric care.'

Now the reporter wants to know whether Malcolm X suggests using violence. The benign expression vanishes and his eyes become fierce. 'We don't advocate violence, but non-violent tactics based solely on morality can only succeed when you are dealing with a basically moral people,' he explains. 'A man who oppresses another man because of his color is not moral. It is the duty of every Afro-American to protect himself against mass murderers, bombers, lynchers, floggers, brutalizers and exploiters. If the government is unable or unwilling to protect us, we reserve our right as citizens to defend ourselves by whatever means necessary. A man with a rifle or club can only be stopped by a person armed with a rifle or club.' The last two sentences are accompanied by a staccato of thrusts with his ballpoint pen.

'Is it true that you were ousted by the Black Muslims because of disparaging remarks about President Kennedy's assassination?'

'That wasn't the reason at all. I was quoted out of context, but I have made stronger statements before and nobody objected. The real reason was jealousy of my growing influence and my objections to a breakdown of morality.' He refers to the paternity suits filed by two women in Los Angeles against 67-year-old Elijah Muhammad in which they charge the cult leader with having fathered their children while working for him as secretaries.

'What future do you foresee for the Black Muslim movement?'

'None. The only thing that held the movement together was the image of mortality reflected by Mr. Muhammad.' Malcolm X pointedly omits 'the honorable,' a standard prefix in his references to his former chief before the break. 'The Black Muslim movement will crumble,' he continues, 'because the organization is held together by coercion, by a Gestapo-type police force within its own ranks.'

Malcolm looks at his wrist watch and rises. The interview has come to an end.

Paradoxically, despite the flood of pronouncements that pours from his lips, Malcolm X has remained an enigma to the public, perhaps even to himself. Is he a charlatan or savior, an opportunist or sincere leader dedicated to the liberation of his race? Is he a genius or a slickster with a gift for eloquence? Is his power real or imagined by a sensation-mongering press? Almost everybody ventures to guess, but nobody really knows.

To gauge Malcolm X, the man, requires an intimate knowledge of the forces that shaped him--klan brutality, hunger, slums, alcohol, dope, prostitution and, finally, rehabilitation through Elijah Muhammad's message of a pro-Black Allah. Above all, it calls for an acquaintance with the Black Muslim movement which he helped create and which, in turn, created him. It is that group of people whose misery has caused them to accept the rigid disciplines laid down by Elijah Muhammad in order to escape the frustrations inherent in being Black in White, race-conscious U.S.A. Their utopian goal of building a separate state within the boundaries of the United States has drawn condescending smiles from both Whites and integration-minded Blacks alike. But their militant assertion to engage the 'White devils' in a mortal battle if attacked has not. It has made Whites uneasy and struck a chord of empathy among Blacks throughout the nation in all walks of life.

The man who became the most articulate proponent of this militancy, who for 12 years spread Elijah Muhammad's incendiary prophecy of doom for the White race and salvation for Blacks, is Malcolm X. He was born 39 years ago in Omaha, Neb., and given the name Malcolm Little. His father, the Rev. Earl Little, an obscure Baptist preacher, spent more time recruiting followers for Marcus Garvey's back-to-Africa movement than for Jesus Christ. There were 10 children (six boys and four girls) in the Little clan.

Malcolm's opinion of 'White devils' was formed early in life, partially by events that occurred even before he was born. 'My father was the color of this,' he recalls, pointing to his Black shoes, 'and my mother, whose mother was raped by a White man, was light enough to pass for White. I hate every drop of White blood in me because it is the blood of a rapist.'

He had hardly learned to walk when he heard his mother's vivid accounts of being victimized by the Ku Klux Klan. 'My father was away on an organizing trip and my mother was pregnant with me when klansmen on horseback came looking for him in the middle of the night. Before they left, they smashed every window in our house.'

The Rev. Little took the klan's 'hint,' and as soon as Malcolm was born, he moved with his family to Milwaukee, Wis., and resumed his organizing activities. Before long he had made enough enemies among Whites to find it advisable to skip town again. This time, the Littles moved to Lansing, Mich., into an all-White neighborhood. 'We hadn't lived there a year,' Malcolm remembers, 'when our home was burned to the ground. Luckily we got out.' The worst was yet to come. Two years after the fire, the Rev. Little was found bludgeoned to death under a street car. The killing, Malcolm says, was officially listed as a traffic accident. 'I was only six years at the time, but I had already learned that being a Negro in this country was a liability.'

When he was 11 years old, Malcolm, 'dizzy from hunger most of the time' ran away from home. Already, the major portion of his formal education--most of it in an all-White country school--was a matter of the past. He tramped to Mason, Mich., where he moved in with a sympathetic Black family. 'Soon I was wayward and on the way to reform school,' he recalls. But fate intervened in the form of a 'White devil' in the guise of a kind lady, the director of the detention home to which he had been sent. 'That woman liked me and let me stay in her home with her family,' Malcolm says. 'But she liked me like one likes a canary or chihuahua--not like a human being.' Tired of being a White woman's 'mascot,' little Malcolm skipped town. Somehow, he made it to the Boston home of a half-sister, who promptly enrolled him in the eighth grade of an all-boys school. 'In those days,' says Malcolm, 'I was very interested in little girls. So when I looked around in my class and all I saw was boys, I just walked out. I haven't been back to school since.'

Malcolm began to roam the streets of Boston, finally landed a job on the railroad by putting up his age. He was 15 years old at the time, but 'looked big and old enough to pass for 21.' Starting as a handyman in the commissary, he eventually advanced to fourth cook--'a euphemism for dishwasher.' In that capacity he made runs on the Colonial between Boston and Washington, D.C., and later on the Yankee Clipper to New York. The cooks and waiters he met on his runs took a liking to the lanky, sandy-haired youth and treated him like a peer. 'That grew me up real fast,' says Malcolm, 'because in those days, railroad men were about the hippest people in town.' During stops in New York, he discovered and explored a strange and fascinating world--Harlem. 'Within a year on the road I had grown so wild that waiters made bets that I wouldn't live another year,' he says.

Frequently neglecting his duties, he was fired from his job. He no longer needed or, for that matter, wanted one, because now he was a 'man with connections' on the way to the big time. The 'big time' was night clubs, bars and dance halls and his 'connections' were barkeeps, waiters, street walkers, dope peddlers and pimps. 'Anywhere there was a dance,' he says, 'I was there. I practically lived in night clubs.' At 18 Malcolm Little had become 'Big Red.' His philosophy at the time: 'The only thing that is wrong is what you are caught doing wrong.'

Although Harlem remained his regular beat, he still traveled a great deal, using his void railroad pass instead of money. 'I could jive any train conductor into letting me on,' he says. 'I had a jungle mind and everything I did was done by instinct to survive.'

He started smoking reefers and finally sold them. His 'jungle mind' did not let him stop there. 'I knew all the important and respected White people downtown. They used to come to Harlem to get their kicks. Most of them wanted Negro women and to get high; I got them whatever they wanted. I used to sell Black women to White men and White women to Black men,' he admits. Sensing the status value of 'having' a White woman in those days, he made sure to keep a liberal supply for himself. 'My respect for White people--particularly White women--dropped lower and lower as I watched how they carried on. Black women had to get drunk to do what White women did sober.'

Toward the end of 1945, Malcolm went to Boston. There, easy money, and with it his luck, ran out. 'I needed some cash real bad,' he remembers, 'so I went to work with my integrated burglar gang, including a woman. One day, I took an expensive, stolen gold watch to a jewelry store to have the crystal repaired. When I went to pick it up, there was a cop waiting for me to arrest me. I always carried a gun, but something told me not to use it. That saved my life, for as we reached the street, I saw that the place was surrounded by cops. Had I used the gun, I would never have left that store alive.'

Malcolm was convicted for burglary and got eight to ten years in the Charlestown State Prison in Boston. When the judge sentenced him, he recalls, he cracked: 'This will teach you to stay away from White girls.' It not only taught him to stay away from White girls, but from White people, period.

After a year in Charlestown State, he was transferred to the Concord (Mass.) Reformatory and, after another year, to the Norfolk (Mass.) Prison Colony. Even in prison, he continued to stay 'high' on dope and booze. 'You know,' he says, 'you can get anything in prison that you can get in the streets if you know how to operate.' A cum laude graduate of Harlem's vice dens, Malcolm knew 'how to operate.' The person he credits with helping him 'come down and get out of the fog bag I was in' was a fellow prisoner--an atheist intellectual. 'At the time, the extent of my reading was cowboy books,' Malcolm admits. 'This guy started me reading serious books--you know, books with intellectual vitamins.' Soon Malcolm became the most frequent visitor to the prison library, devouring volume after volume, from Shakespeare to Hegel and Kant. He beefed up his reading with correspondence courses in English and German and by attending prison school, a facility most prisioners patronized merely to break the monotony of the cell. But Malcolm was a serious student. 'Language became an obsession with me,' he remembers. 'I began to realize the meaning and the power of words.'

While in jail, Malcolm kept corresponding with his brothers, Philbert and Reginald. Both had become converts of Elijah Muhammad's Black Muslim cult. His eldest brother, Reginald, wrote him that if he ever wanted to get out of jail, he should 'stop smoking and eating hog.' Having always looked up to his brother, Malcolm took his advice. Within a year, after serving 77 months--just seven months short of seven years--Malcolm was paroled.

The year was 1952 and Malcolm went to Detroit to live with Philbert and Reginald. Eventually he, too, joined the Black Muslims at Detroit Mosque No. 1.

Like all practicing Black Muslims, Malcolm shed his 'slave name,' Little, and substituted it with an 'X' (for exslave). Along with his name, he shed his vices--alcohol, nicotine, dope, women and 'hog.' Obediently he prayed five times daily facing Mecca and observed Elijah Muhammad's dictates of keeping 'a clean body, a clean mind, clean speech and a clean home.' The transformation was complete. The 'Christian sinner' Malcolm Little alias Big Red had become the ascetic Black Muslim Malcolm X.

'When I joined, I don't think there were more than 400 Black Muslims in the entire country--most of them older people,' Malcolm X maintains. 'At that time, Mr. Muhammad stayed pretty much in the background. Many of the brothers couldn't even pronounce his name. Instead of revering him, they all prayed for the return of Wallace Fard (an itinerate silk peddler who started the movement in 1932 and mysteriously disappeared in 1934).'

Malcolm X changed all that. 'Mr. Muhammad agreed to let me present him as the prophet and messenger of Allah. I personally believed in Mr. Muhammad because my brother Reginald believed in him and I believed in Reginald. Soon the people I talked to believed in Mr. Muhammad, too.'

For 12 years, Malcolm X talked, honing his natural gift for oratory and debate to the keenness of a switchblade knife. Aided by a computer-like brain that can store and recall at will volumes of encyclopaedic facts, he slashed at White racism, taking on everyone from 'Uncle Tom Negroes' to the U.S. Government. Wherever he talked, new Black Muslim temples sprang up while already existing ones increased their memberships. To be sure, not all of his converts comprehended his mystic teachings of Black Islam, but his provocative demands for 'back pay for 400 years of slave labor' made sense to all.

Today, many of his explosive statements have been modified. He even concedes that his one-time perennial target--the NAACP--'is doing some good.' He makesit abundantly clear that he still hates, but says that his hatred is now confined to those who hate Blacks. Until put to a real test, the true intentions of Malcolm X--like the man himself--will remain shrouded in speculation and mystery. Only one thing is clear: neither the Black Muslim movement without him, nor the Civil Rights Movement with him will ever be the same.

COPYRIGHT 1993 Johnson Publishing Co.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group

Malcolm X interviewed on Front Page Challenge, a long running (1957-1995) CBC show, in which journalist panelists guessed the identity of a news figure, and then interviewed the person (Aired January 5, 1965)

Malcolm X, Pierre Berton

[transcript here]

January 19, 1965

PIERRE BERTON: At the time of President Kennedy's assassination, you made a speech that seemed to indicate that you were pleased that he had been assassinated. Certainly at that time, Elijah Muhammad indicated that you had been fired or suspended from the Black Muslim movement. How about that?

MALCOLM X: I had taken a subject as my topic that day, an approach that was designed to show that the seeds that America had sown–in enslavement, in many of the things that followed since then–all of these seeds were coming up today; it was harvest time. At the end of this particular lecture, during the question-and-answer period, somebody asked me what I thought of the assassination of President Kennedy. In line with the topic that I had just been discussing, I pointed out that it was a case of the chickens coming home to roost, by which I meant that this was the result of seeds that had been sown, that this was the harvest. This was taken out of context, and reported in one of the papers, and Elijah Muhammad, who had been waiting for me to make a move that would enable him to suspend me and get the support of the public in doing so, took advantage of that opportunity. He gave the impression that I was saying something against the president himself because he felt that the public wouldn't go along with that.

BERTON: How did you feel, personally, about the president's assassination in that connection? Were you bothered about it? Were you angered by it? Or were you jubilant?

MALCOLM X: No. I was realistic, in that being at the forefront of this struggle of the black man in America–in his quest for respect as a human being–I had seen the many-faceted repercussions of this hate taking a grip on the American public. I think that many of the politicians took advantage of it and exploited it for their own personal benefit. So to me the whole thing was a case of politics, hate and a combination of other things.

BERTON: There seems to me to have been a fair amount of hate in the Black Muslim movement itself.

MALCOLM X: Well, I won't deny that. But, at the same time, I don't think that the Black Muslim movement and its hate can be classified as the same degree or type of hate you find in the American society itself, because the hate, so-called, that you see among black people is a reaction to the hate of the society which has rejected us. In that sense it is not hate.

BERTON: I'm not saying that the hate, or whatever it is, isn't understandable. I'm asking if it's effective to fight hate with hate?

MALCOLM X: In my opinion, I think that it is not fair to classify the reaction of people who are oppressed as hate. They are reacting to the hate of the society they have had put upon them or practiced against them....

BERTON: . . . Let me ask you this about your God, Mr. X. Has he got any color? Is he black?

MALCOLM X: No.

BERTON: Is he white?

MALCOLM X: As a Black Muslim, who believed what Eljah Muhammad taught, I regarded God just as he taught, as a black man. Having since gone into the Muslim world and got a better understanding of the religion of Islam, I believe that God is the supreme being, and that color plays no part in his particular being.

BERTON: In fact, isn't the God of the Muslims and of the Jews and the Christians really the same God?

MALCOLM X: If they believe in the God who created the universe, then we all believe in the same God. I believe in the God who created the universe. Muslims call him Allah. Christians, perhaps, call him Christ, or by some other name. Jews call him Jehovah, and in referring to him they mean 'the creative.' We are all referring to the same God.

BERTON: Now, let me switch the subject briefly, and ask you what you mean when you say that the Black Muslims are not militant enough. Your new organization, I take it, will be more militant than the Black Muslims. In what way?

MALCOLM X: Well, the Black Muslim movement, number one, professes to be a religious movement. They profess the religion of Islam. But the Muslim world rejected the Black Muslim movement as a bona fide Islamic group, so it found itself maneuvered into a religious vacuum–or a sort of religious hybrid. At the same time, the government of the United States tried to maneuver the Black Muslim movement, with the press, into an image that was political instead of religious. So the Black Muslim movement came to be known as a political group. Yet, at the same time, it didn't vote; it didn't take part in any politics; it didn't involve itself actively in the civil rights struggle; so it became a political hybrid as well as a religious hybrid. Now, on the other hand, the Black Muslim movement attracted the most militant black American, the young, dissatisfied, uncompromising element that exists in this country–drawing them in yet, at the same time, giving them no part to play in the struggle other than moral reform. It created a lot of disillusion, dissatisfaction, dissension, and eventually division. Those who divided are the ones that I'm a part of. We set up the Muslim Mosque, which is based upon orthodox Islam, as a religious group so that we could get a better understanding of our religion; but being black Americans, though we are Muslims, who believe in brotherhood, we also realized that our people have a problem in America that goes beyond religion. We realized that many of our people aren't going to become Muslim; many of them aren't even interested in anything religious; so we set up the Organization of Afro-American Unity as a nonreligious organization which all black Americans could become a part of and play an active part in striking out at the political, economic, and social evils that all of us are confronted by.

BERTON: That 'striking out,' what form is it going to take? You talk of giving the Ku Klux Klan a taste of its own medicine. This is in direct opposition to the theory of nonviolence of Dr. Martin Luther King, who doesn't believe in striking back. What do you mean by 'a taste of its own medicine'? Are you going to burn fiery crosses on their lawns? Are you going to blow up churches with the Ku Klux Klan kids in them? What are you going to do?

MALCOLM X: Well, I think that the only way that two different races can get along with each other is, first, they have to understand each other. That cannot be brought about other than through communication dialogue– and you can't communicate with a person unless you speak his language. If the person speaks French, you can't speak English or German.

BERTON: We have that problem in our country, too.

MALCOLM X: In America, our people have so far not been able to speak the type of language that the racists understand. By not speaking that language, they fail to communicate, so that the racist element doesn't really believe that the black American is a human being–part of the human family. There is no communication. So I believe that the only way to communicate with that element is to be in a position to speak their language.

BERTON: And this language is violence?

MALCOLM X: I wouldn't call it violence. I think that they should be made to know that, any time they come into a black community and inflict violence upon members of that black community, they should realize in advance that the black community can speak the same language. Then they would be less likely to come in.

BERTON: Let's be specific here: suppose that a church is bombed. Will you bomb back?

MALCOLM X: I believe that any area of the United States, where the federal government has shown either its unwillingness or inability to protect the lives and the property of the black American, then it is time for the black Americans to band together and do whatever is necessary to see that we get the type of protection we need.

BERTON: 'Whatever is necessary?'

MALCOLM X: I mean just that. Whatever is necessary. This does not mean that we should go out and initiate acts of aggression indiscriminately in the white community. But it does mean that, if we are going to be respected as human beings, we should reserve the right to defend ourselves by whatever means necessary. This is recognized and accepted in any civilized society....

BERTON: There are some people going to go on trial in Mississippi for the murder of three civil rights workers. There are some witnesses who identify them as murderers, but the general feeling is they'll get off. Will you do anything about this if they get off?

MALCOLM X: I wouldn't say.

BERTON: You don't want to say?

MALCOLM X: Because, then, if something happened to them, they would blame me. But I will say that in a society where the law itself is incapable of bringing known murderers to justice, it's historically demonstrable that the well-meaning people of that society have always banded together in one form or another to see that their society was protected against repetitious acts by these same murderers.

BERTON: What you're talking about here is a vigilante movement.

MALCOLM X: There have been vigilante movements forming all over America in white communities, but the black community has yet to form a vigilante committee. This is why we aren't respected as human beings.

BERTON: Are you training men to use aggressive methods? Are you training men as the Black Muslim movement trained the elite core known as the Fruit of Islam? Have you got trainees operating now who know how to fight back?

MALCOLM X: Yes.

BERTON: Who know how to use knuckle-dusters and guns?

MALCOLM X: Yes, oh yes. The black man in America doesn't need that much training. Most of them have been in the army–have already been trained by the government itself. They haven't been trained to think for themselves and, therefore, they've never used this training to protect themselves.

BERTON: Have you got a specific cadre of such young, tough guys working for you or operating under your aegis?

MALCOLM X: We're not a cadre, nor do we want it to be felt that we want to be tough. We're trying to be human beings, and we want to be recognized and accepted as human beings. But we don't think humanity will recognize us or accept us as such until humanity knows that we will do everything to protect our human ranks, as others will do for theirs.

BERTON: Are you prepared to send flying squads into areas where the Negroes have been oppressed without any legal help?

MALCOLM X: We are prepared to do whatever is necessary to see that our people, wherever they are, get the type of protection that the federal government has refused to give them.

BERTON: Okay. Do you still believe that all whites are devils and all blacks saints, as I'm sure you did under the Black Muslim movement?

MALCOLM X: This is what Elijah Muhammad teaches. No, I don't believe that. I believe as the Koran teaches, that a man should not be judged by the color of his skin but rather by his conscious behavior, by his actions, by his attitude towards others and his actions towards others.

BERTON: Now, before you left Elijah Muhammad and went to Mecca and saw the original world of Islam, you believed in complete segregation of the whites and the Negroes. You were opposed both to integration and to intermarriage. Have you changed your views there?

MALCOLM X: I believe in recognizing every human being as a human being, neither white, black, brown nor red. When you are dealing with humanity as one family, there's no question of integration or intermarriage. It's just one human being marrying another human being, or one human being living around and with another human being. I may say, though, that I don't think the burden to defend any such position should ever be put upon the black man. Because it is the white man collectively who has shown that he is hostile towards integration and towards intermarriage and towards these other strides towards oneness. So, as a black man, and especially as a black American, I don't think that I would have to defend any stand that I formerly took. Because it's still a reaction of the society and it's a reaction that was produced by the white society. And I think that it is the society that produced this that should be attacked, not the reaction that develops among the people who are the victims of that negative society.

BERTON: But you no longer believe in a Black State?

MALCOLM X: No.

BERTON: In North America?

MALCOLM X: No. I believe in a society in which people can live like human beings on the basis of equality.

and reconciled with Martin Luther King Jr.

Related Posts:

Saudi Arabia and Hajj

Eid Al-Adha

Hajj and Eid Al-Adha 2009—The Unforeseen: A Deluge of Rain and Flooding

Hajj--Some Elements of a Pictorial History: 7th-19th Centuries; 1885 Photos

Hajj and Health: Saudi Religious and Medical Leadership Prevails Over Religious Misinformation About Polio Vaccination

Your comments, thoughts, impressions?

Have you had or known of a transformational experience of Hajj?

What are your impressions of Malcolm X and his legacy?

Do the white interviewers seem more frightened of Malcolm X's ideas than the black Hans Massaquoi?

Was Malcolm X's message to both Black American and White Canadian audiences in this series of interviews essentially consistent?

Other ideas?